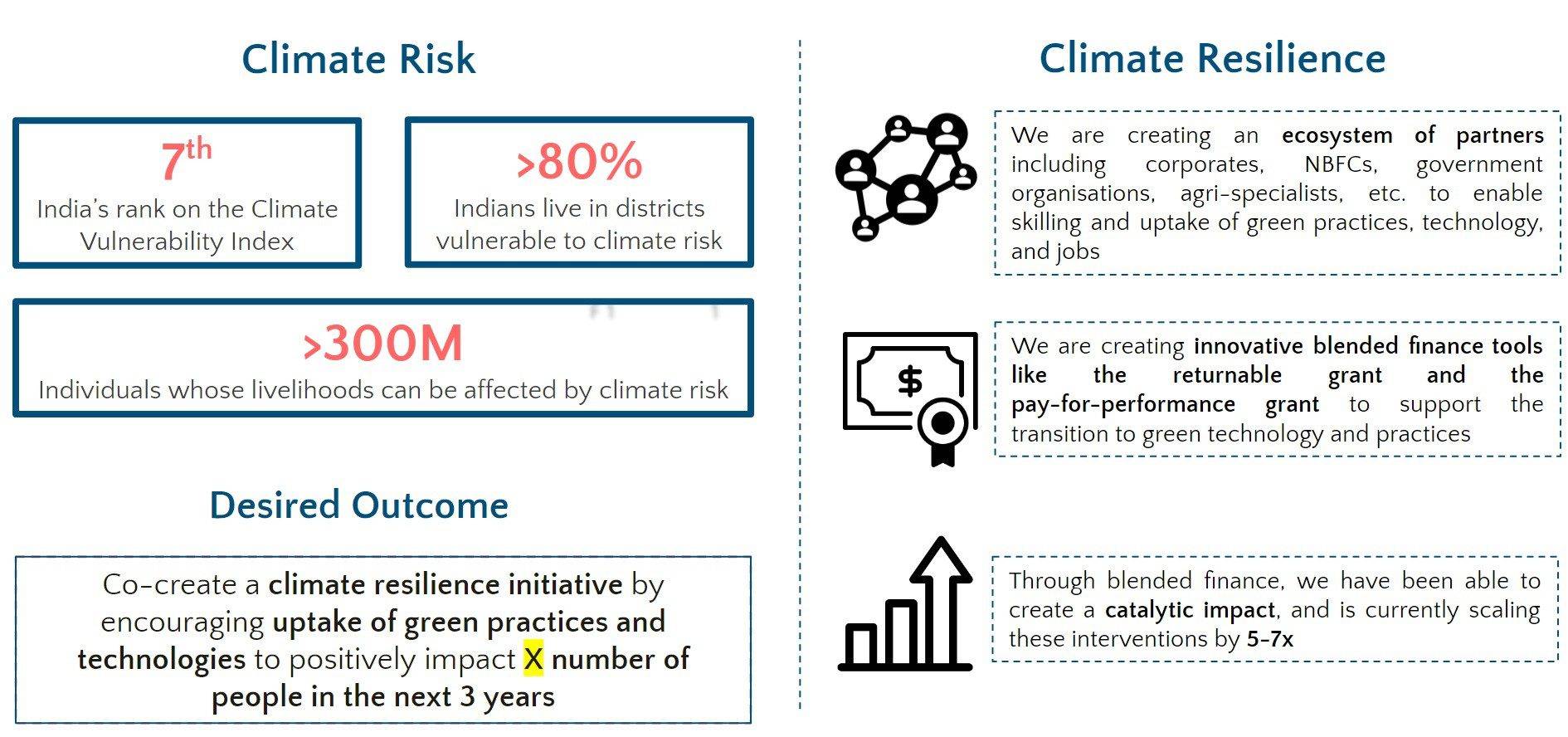

What companies need to keep in mind to ensure that their skilling programs are effective and impactful.

According to Labour Bureau of the Government of India, 90% of the 450 million jobs in India require vocational skills. And right now only 10% of the workforce receive any kind of vocational training at all, formal or informal.[1]

Compare India�s present scenario to those living in developed countries, where 75% undergo formal skill training and it�s clear that we need to do a lot of catching up.

The Skill India Mission presents a unique opportunity for companies to leverage their core business competencies and contribute to skilling India. Part I of this series on Livelihoods and Skill Development, discussed why it is critical for companies to align with the Mission and join together in a concerted effort to close the skills gap in the country�s labour force.

In Part II, we look at what companies need to keep in mind when implementing training programs as part of the Skill India Mission.

The Mission is a new opportunity for companies as it is different from past efforts by the government in a number of ways. Most critically it has consolidated the skilling effort in India by replacing the 20-odd ministries that were previously engaged with training programs with one focused and central Ministry for Skill Development and Entrepreneurship (MSDE). The MSDE has its own budget and is mandated to drive skill development efforts in the country, by co-ordinating the programs of State Governments and other Ministries. The MSDE also collaborates with companies in the private sector, developing frameworks for vocational and technical training and planning for skills that may be required in the future.

The Skill India Mission prioritizes aspects of skilling that were previously ignored, like the recognition of prior experience and entrepreneurship skills. Rajesh Kaimal, Business Head of Manipal City and Guilds, an education service provider that trains and certifies people across the country, points out that under the new initiative, �there is a special focus on RPL (Recognition of Prior Learning), which is a drive to recognise people who are already well-versed in a trade but don�t have any formal certification.� Under the PMKVY, a scheme under the MSDE, there is an equal emphasis on RPL skill training programs. Out of the 24 lakh (2.4 million) people that the scheme aims to train each year, 12 lakh (1.2 million) has been earmarked for training and assessment and 12 lakh for the recognition of prior learning.

Praveen Aggarwal, the Chief Operating Officer of Swades � a foundation that focuses on creating livelihood opportunities for rural populations � commended the creation of a separate policy to encourage entrepreneurship.

Under the mandate, the MSDE is directed to make entrepreneurship aspirational and encourage it as a viable career option through advocacy, create support networks for potential entrepreneurs and promote entrepreneurship amongst women. Mr. Aggarwal believed that an equal focus on entrepreneurship skills is especially critical for rural areas and saw this as a good move by the Indian Government.

Getting it right

With the government making a strategic effort to create a skilled workforce and prioritizing skill development initiatives, it is critical that companies also get on board and invest in effective programs. Conducting one-off trainings or failing to link them to jobs may not significantly improve the prospects of those seeking work. From our conversations with a number of companies and implementation agencies in India, we have developed some guidelines that companies may find helpful when developing and executing their skilling programs.

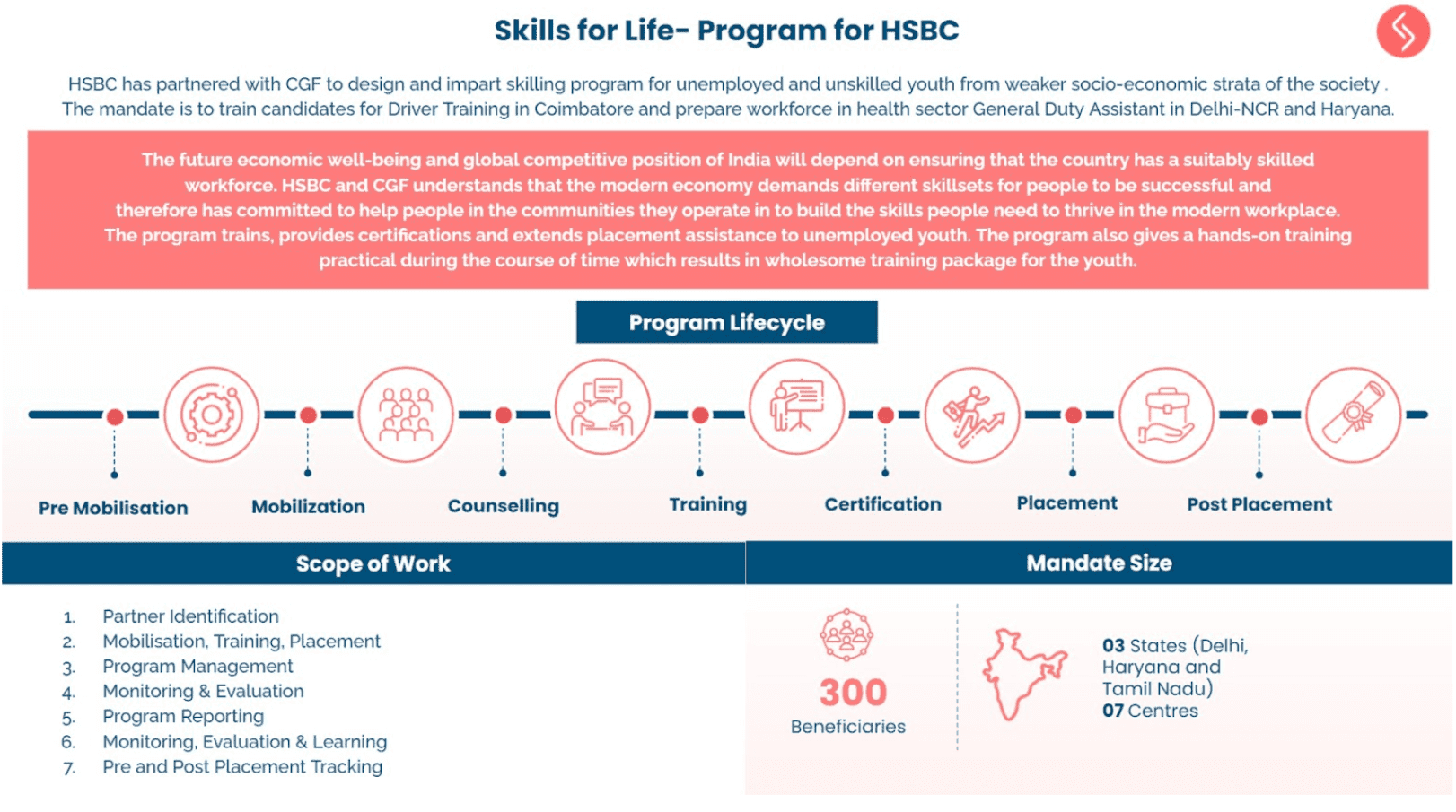

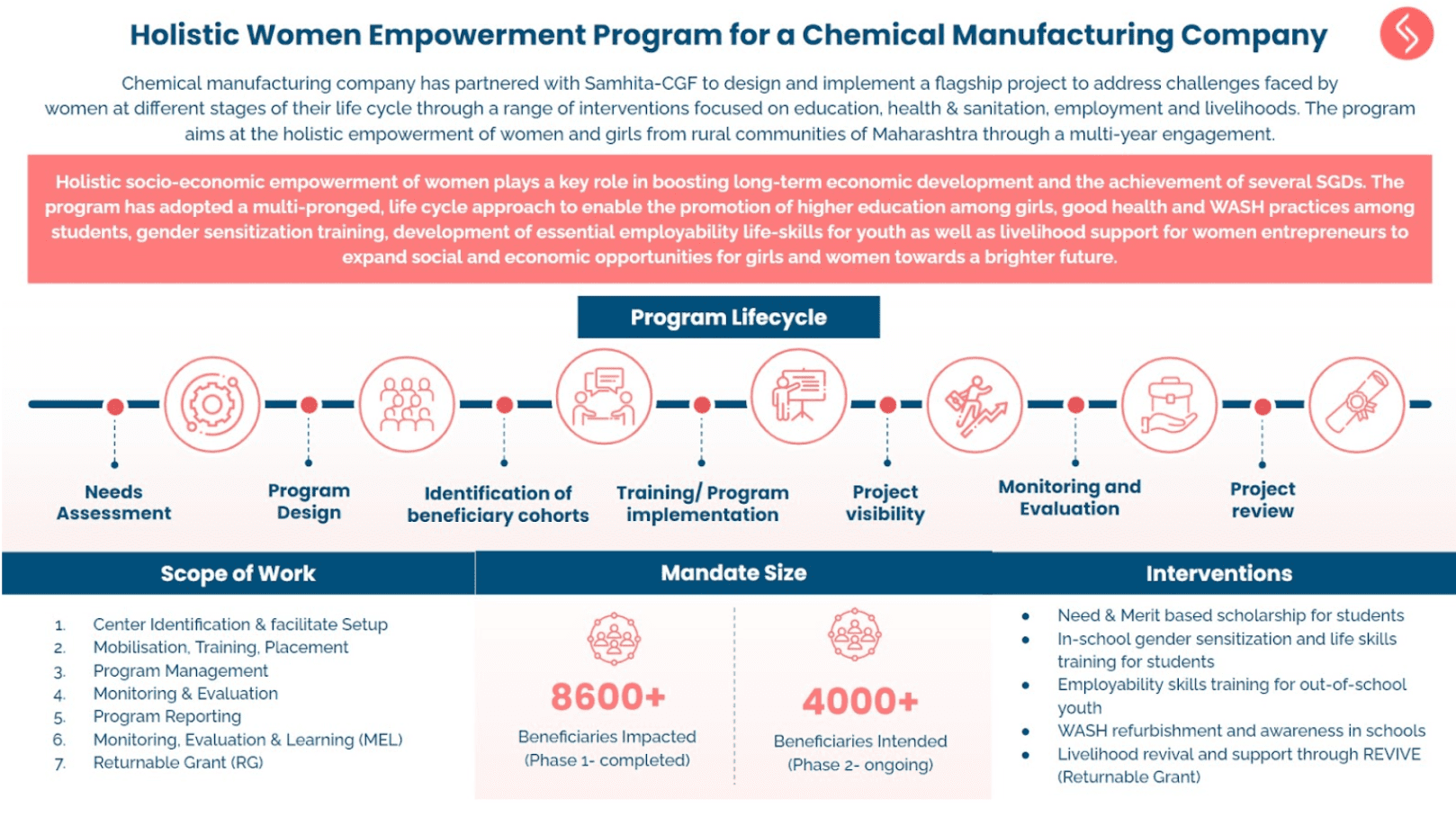

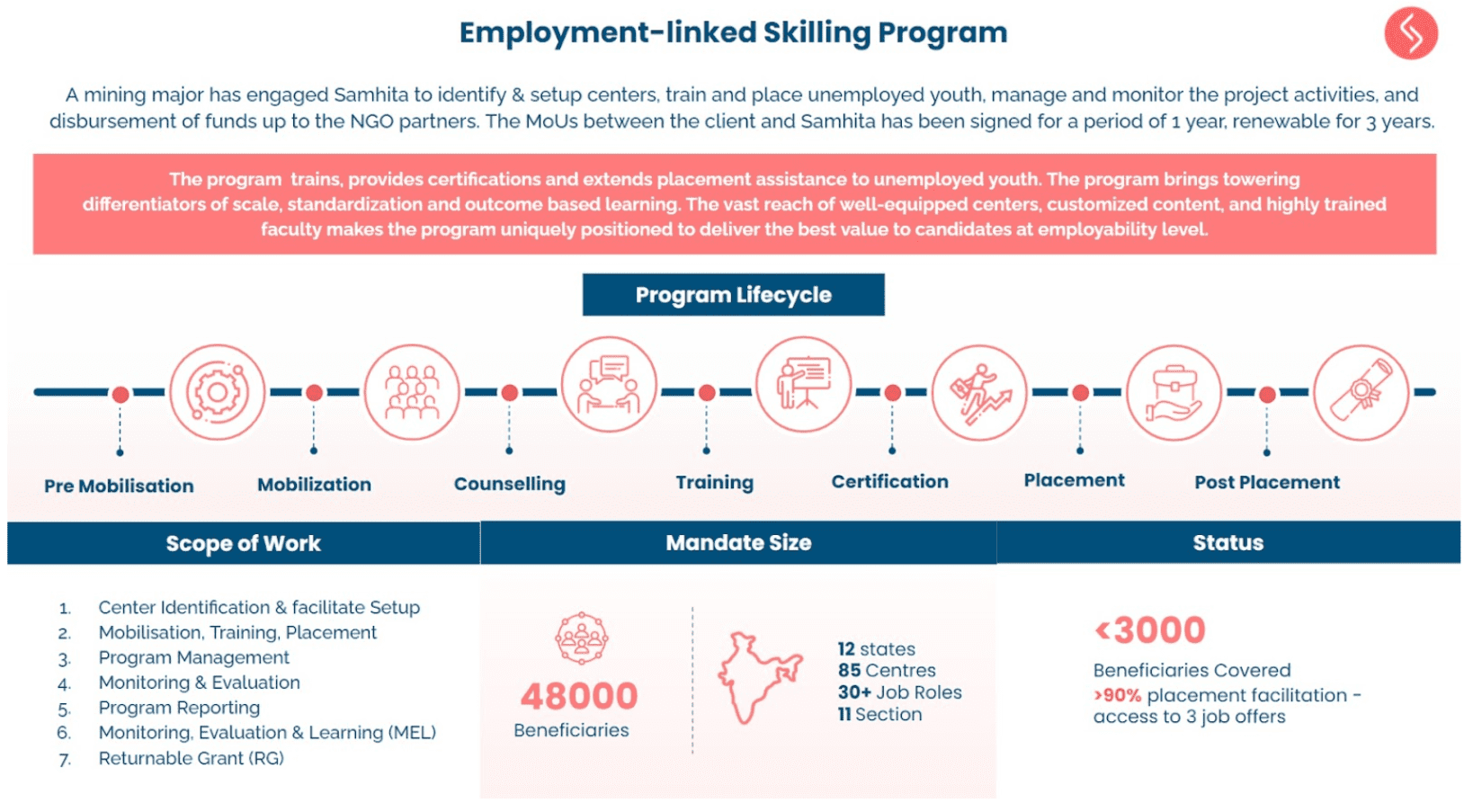

Adopt a lifecycle approach

Like any other intervention in the social sector, in order to achieve long-term impact, companies need to adopt a lifecycle approach to skill development. This means designing programs that look at every aspect of skilling communities and includes mapping the skills and aspirations of a community before training, conducting training that is based on the findings of the skill mapping, connecting trainees to employment opportunities after the training and following up with them after employment. One of the programs that Swades conducts adopts this approach. Apart from the activities listed here, Swades conducts an intensive follow up with their trainees. Once placed in employment Swades tracked the progress of their trainees for 2 years. In the first year tracking occurred on a monthly basis in order to provide �hand-holding� and get them accustomed to an office environment. In the second year, follow-ups were reduced to quarterly intervals. Praveen Aggarwal says that the reason Swades does this is, �to see how they are progressing in their careers and if they leave their jobs, why are they doing this etc.�

Following up with newly employed trainees is especially critical as it can result in significantly reducing the number of people leaving their jobs because of being unable to cope with new work environments.

Match skills to aspirations

Training programs need to keep in mind the marketability of skills received at the end of the course and match them to individual aspirations and desires in order for them to be impactful. Training that is not linked to careers that people want, is a waste of resources on both sides of the equation. A good way to ensure the relevance of training is by mapping skills according to both market needs and local capabilities.

This approach ensures the expectations and requirements of a particular community are met and provides guidelines on what kind of training is needed. Swades ensures that their training is consistently effective by, �giving (people) a bouquet of choices, empowering them with a sense of decision making � of what they can do with their lives, (and) creating aspirations.� Mr. Aggarwal went on to say that attempting to meet the needs of communities and advising them against potentially less-viable career paths, is a fine balancing act.

Transferrable skills: Providing communities with transferrable skills is also useful as it builds competence in areas required for most jobs. Transferrable skills include communication and analytical skills, decision-making abilities, team work, writing and reporting skills and other similar skills. For semi-urban and rural populations, such skills are especially useful as most have never been in an office environment. In their training on transferable skills, Swades includes aspects like how to dress appropriately for different types of employment, basic computer literacy, personal hygiene, interview skills, tackling work under pressure, dealing with superiors, reporting procedures and other useful information.

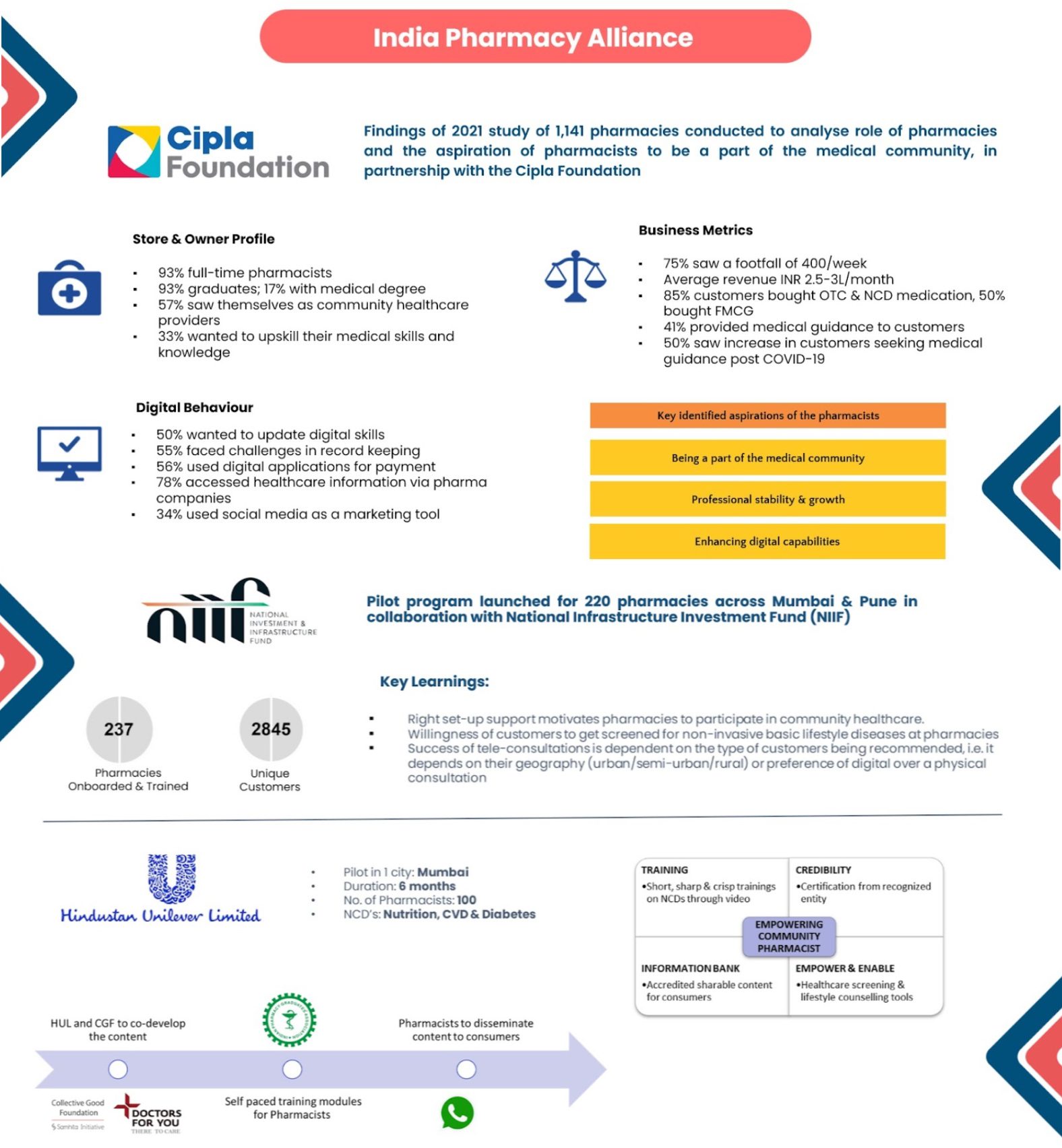

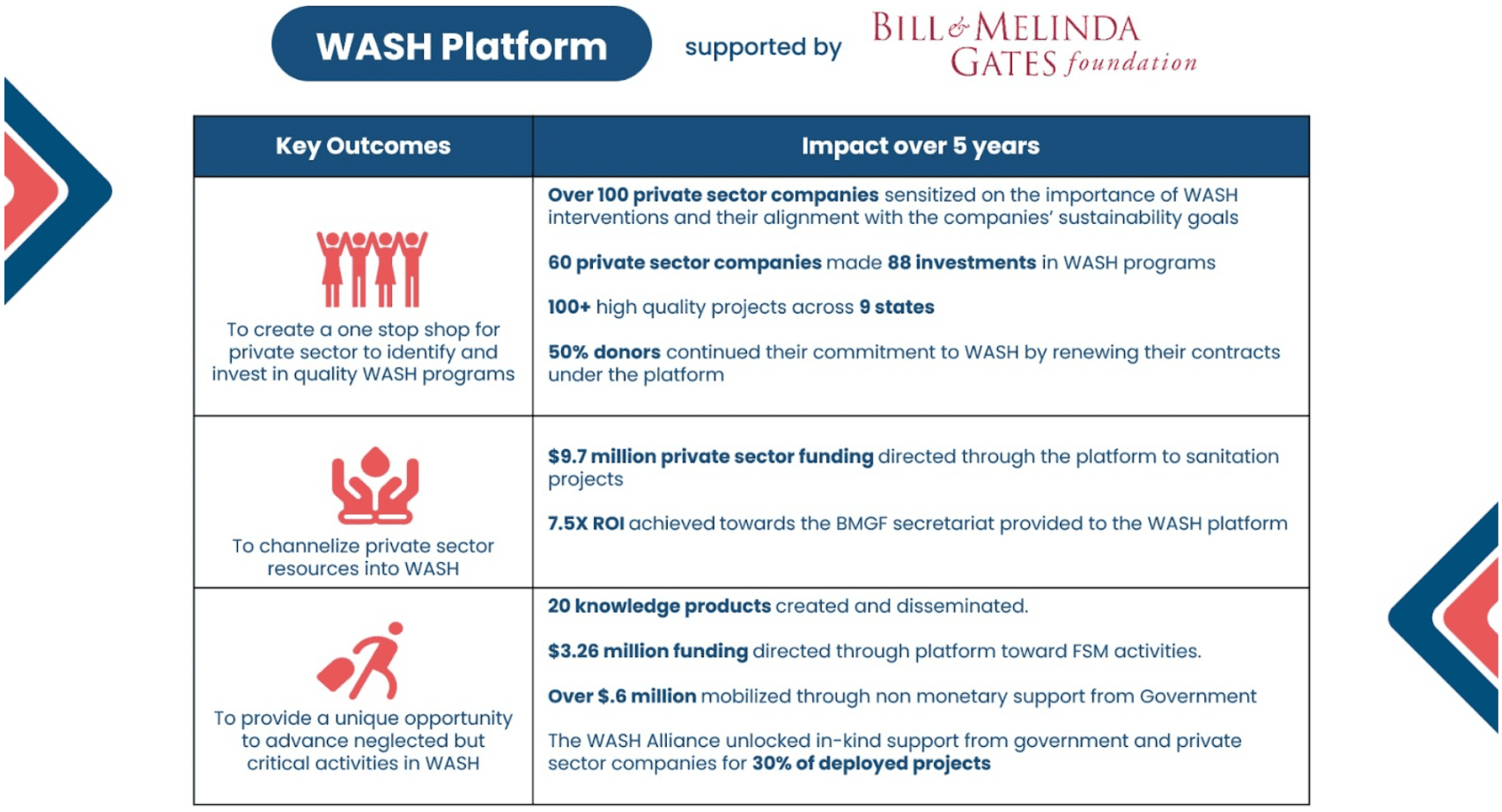

Connecting skills to the market

Providing market-relevant skills to communities should be a key focus area for companies. Without a link to market demands, skill training become redundant. Kalyan Chakravathy from PanIIT Alumni Reach for India (PARFI), a social enterprise that conducts skill training across India, spoke about how they link training to market needs by engaging with CSR, �(While) we work on an institutionalized, long-term, investment-heavy model, it does not mean that we are not consistent with the market. We are very demand-focused (and) update that demand through investment. That�s where CSR comes into the picture. Many of our schools are funded by companies.� PARFI�s skilling model is a loan-based training model which engages companies to provide employment opportunities and gives 100% placement to trainees after their courses. Mr. Chakravarthy said that placements were assured, �because we first sign up the employer and then set up the training.� With companies providing an input on what skills are needed, PARFI is able to conduct training that is relevant and can enhance the career prospects of trainees after the course.

The Value of Skills

If the courses or training that people receive are not recognised as valuable to their personal economic growth, for example by enabling individuals to achieve a higher salary or a better job, then there is very little incentive for them to take part in the program. If a watchman who has been trained under the skilling program subsequently receives the same salary as someone who is not trained, then what value has it added to his personal situation? Linking skill training to market needs is critical but companies must also ensure that this training will add value to the overall career prospects of beneficiaries.

Currently, training institutes across India are seen negatively as purely manpower sourcing agencies and this needs to change.

The Swades Foundation tackles this issue by working with select partners and social enterprises who they identify as having an understanding of a specific market. They connect their training to those who have demand for particular skills. PARFI works on a sustainable vocational training model that is loan-driven. The system, although charging trainees a fee, works well as it encourages only those genuinely interested to take part. The fee also ensures a high standard of quality and active participation from trainees, contributing to the overall sustainability of the program � and giving an impetus to social entrepreneurship as a whole.

Many government-sponsored skilling programs see high turnouts but do not necessarily have an impact on workforce skilling levels because they are free and are available to anyone, whether interested in a particular course or not. In general trainees tend not to attach much value to training that is paid for by the government. In the education field in India, people willingly pay more to be taught privately despite the considerable financial constraints this may place on them and their families. But they are prepared to do this because more often than not, the qualification they receive from a private institution will lead to more opportunities and a better standard of living.

The skilling centres of the future should be structured in such a way that the quality of their training is perceived as highly desirable and consequently valued by both potential trainees and future employers.

Focus on Entrepreneurship

Another way to look at the economic development of communities, especially those in rural areas, is through increased entrepreneurship. In 2013-14, agriculture employed 54% of the workforce in India but only contributed to 17% of the GDP[2]. In such a context, where the supply of labour outweighs demand by a large margin, finding new means of employment can be critical.

Providing rural communities with entrepreneurship skills and helping them start cottage industries or small businesses could work to supplement existing income and create local employment for many who would otherwise be forced to migrate to cities. Swades looks at building the entrepreneurship ecosystem by enabling entrepreneurs to create their own value chains. For companies, entrepreneurship programs are trickier as they need to establish connections to the market in order to provide entrepreneurs with a space to sell their products. Before implementing such programs it is important that companies ensure that implementation partners have a connection to the market and a clear exit strategy that enables the local community to continue work once the program has ended. Swades� Praveen Aggarwal continued, �We are trying to create an entrepreneurship ecosystem. We manage the entire process�including providing entrepreneurship skills, how to understand your market, profit and loss, how to keep your account books��

The added focus on entrepreneurship by the MSDE also presents a way for companies to leverage the entrepreneurship policy (see above) and engage with such programs.

Systemic Problems

One of the challenges of the current vocational training system is the lack of proper exit mechanisms for students of such programs. Rajesh Kaimal, Manipal City & Guilds (MCG), talks about the challenges of this situation, �a student who is on an engineering or an ITI course, should be able to exit after 1 or 2 semesters. [They should be able to] get a vocational education, get a certificate and then at some point take those credits and return to the formal education system and vice-versa. Most students drop out in-between, because courses last 3-4 years and they are unable to complete them because of family pressures or financial difficulties. If a student has done 2 years of a 3 year course and he leaves, he has nothing to show in terms of a qualification. For example � he might do the first year of a masonry course and if he leaves, he has nothing to show in the job market. There needs to be a an officially recognised certificate saying that he is qualified to do something at each step � since there are certain levels to all skills. Today there is no such mechanism and most ITI�s fail today because their students don�t continue.�

Education vs. Experience

When hiring, companies need to look at the value of vocational programs and the experience of applicants rather than exclusively match jobs to the highest level of education they have received (See above). MCG�s Rajesh Kaimal continues, �corporates should recognise that they need skilled people and not (just) educated people and should understand what they want. Is it skills and experience that you require or is it education and a paper degree that you are looking at?� This is a choice that needs to be made wisely by companies. To further illustrate the point, he talked about the fact that former specialized soldiers from the army have been employed as sweepers on the railways, despite having 15 years of experience, and considerable mechanical skills developed by fixing battle tanks. This happens quite often because many join the army straight out of school and consequently do not possess more than a 10th or 12th standard pass certificate. Historically all appointments on the railways have been dictated by an individual�s level of education.

Moving forward: A Vision for Skill Development

The announcement of the new plan for training and skill development is an opportunity that should encourage companies, investors, implementation agencies and potential beneficiaries to rethink traditional approaches to skilling. Even if the aggressive targets for skilling aren�t met, it will be important to ensure that those who pass through programs are trained well and given valuable skills that they can use in the market. It would be a flawed methodology to define the success of future training courses by the number of people being skilled, rather than potential employment outcome. Training people will have little value if they are not ultimately able to find better jobs, earn decent salaries or work in the sector and profile they were trained for � none of which can be achieved without the active involvement of players that dictate demand for skilled labour � namely companies. Why? It is companies that set trends, create demand for specific skills and subsequently understand what is needed for the future as they shape market demand. We need to invest in delivering market-driven skills to the public which will ultimately contribute to the long-term growth and development of the country.

About the contributors:

Praveen Aggarwal, Chief Operating Officer, Swades, a foundation that focuses on creating livelihood opportunities for rural populations across India.

Kalyan Chakravarthy, Executive Director at the PanIIT Alumni Reach for India Foundation (PARFI), a not-for-profit registered society of IIT alumni committed to execute and scale self-sustainable business models that enhance incomes of the underprivileged sections leveraging PanIIT and other like minded networks.

Rajesh Kaimal, Business Head, Manipal City and Guilds, a joint venture between Manipal Education and City & Guilds, UK that trains and certifies people across the country.

Luis Miranda, Director at Samhita Social Ventures and Founder & ex-President, IDFC Private Equity

[1] http://www.tradingeconomics.com/india/gdp-from-agriculture

[2] http://www.tsmg.com/download/article/Skilling%20India%20final.pdf