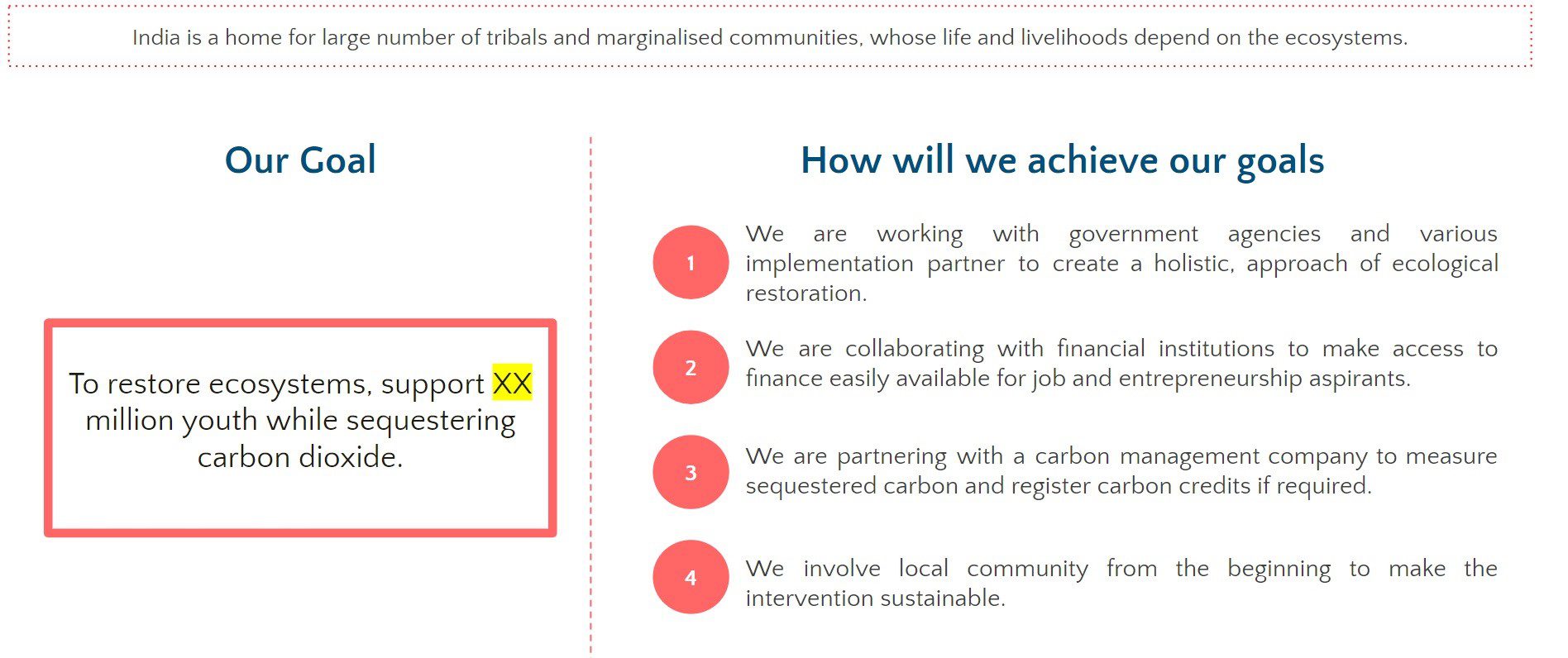

The Blended Finance Continuum: A Catalytic Pathway for Financial Inclusion

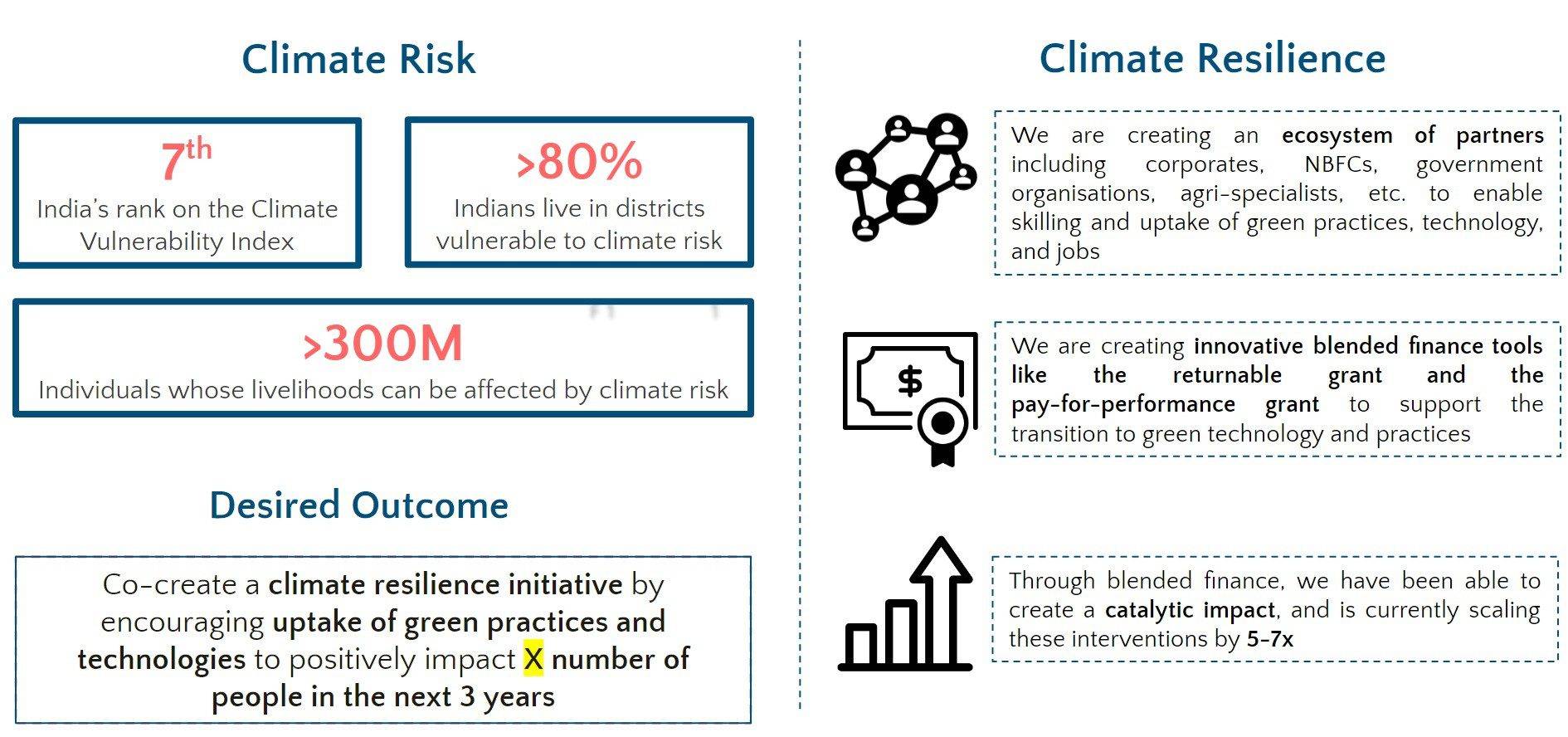

In India, the informal sector represents a significant portion of the workforce, employing more than 90% of workers and contributing around 50% to the country’s GDP. However more than 160 Million Indians remain underserved by formal credit systems

Access to formal credit, economic growth, and financial inclusion are critical for the development and empowerment for entrepreneurs in underserved communities. The lack of credit score and credit history is an impediment for getting credit opportunities, as many lenders are hesitant to extend credit to consumers without any credit history or score.

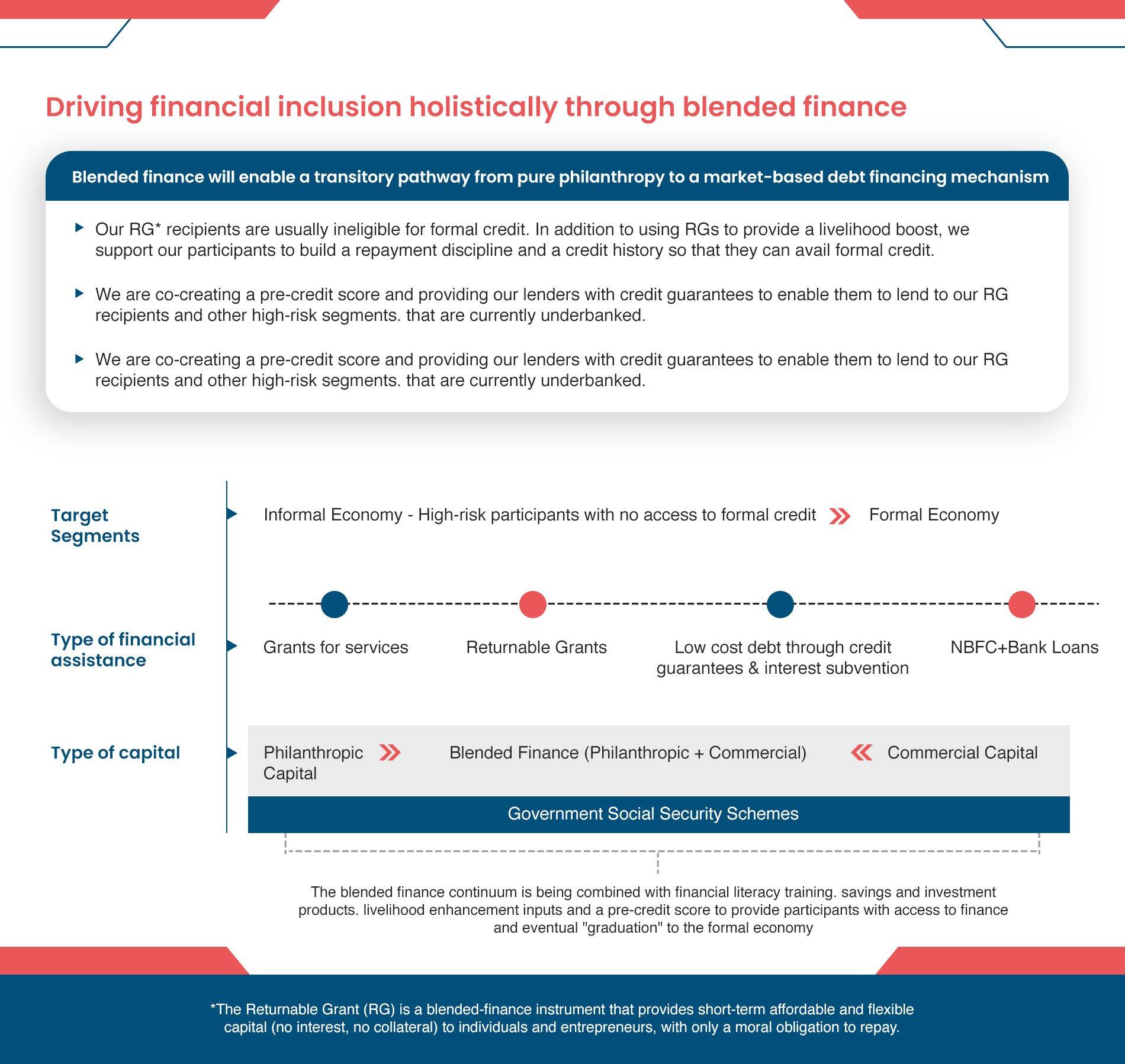

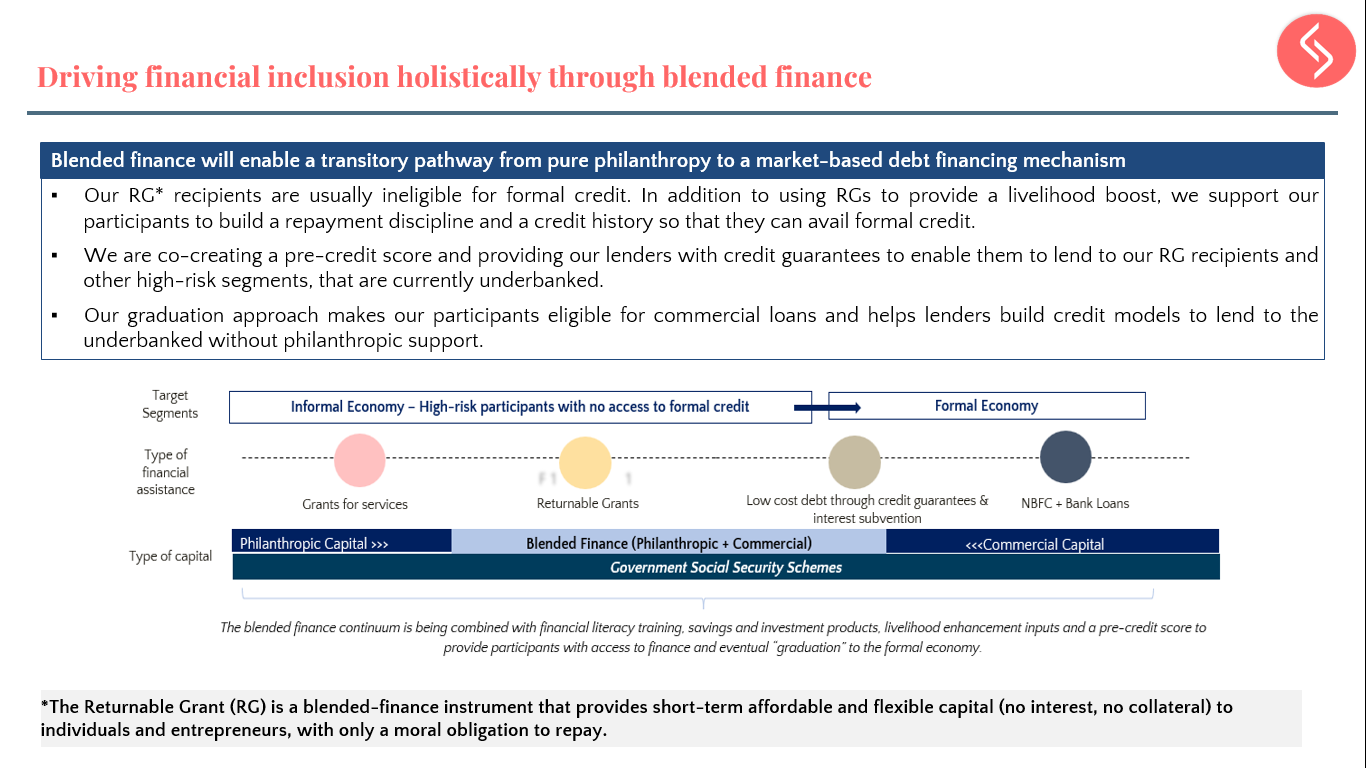

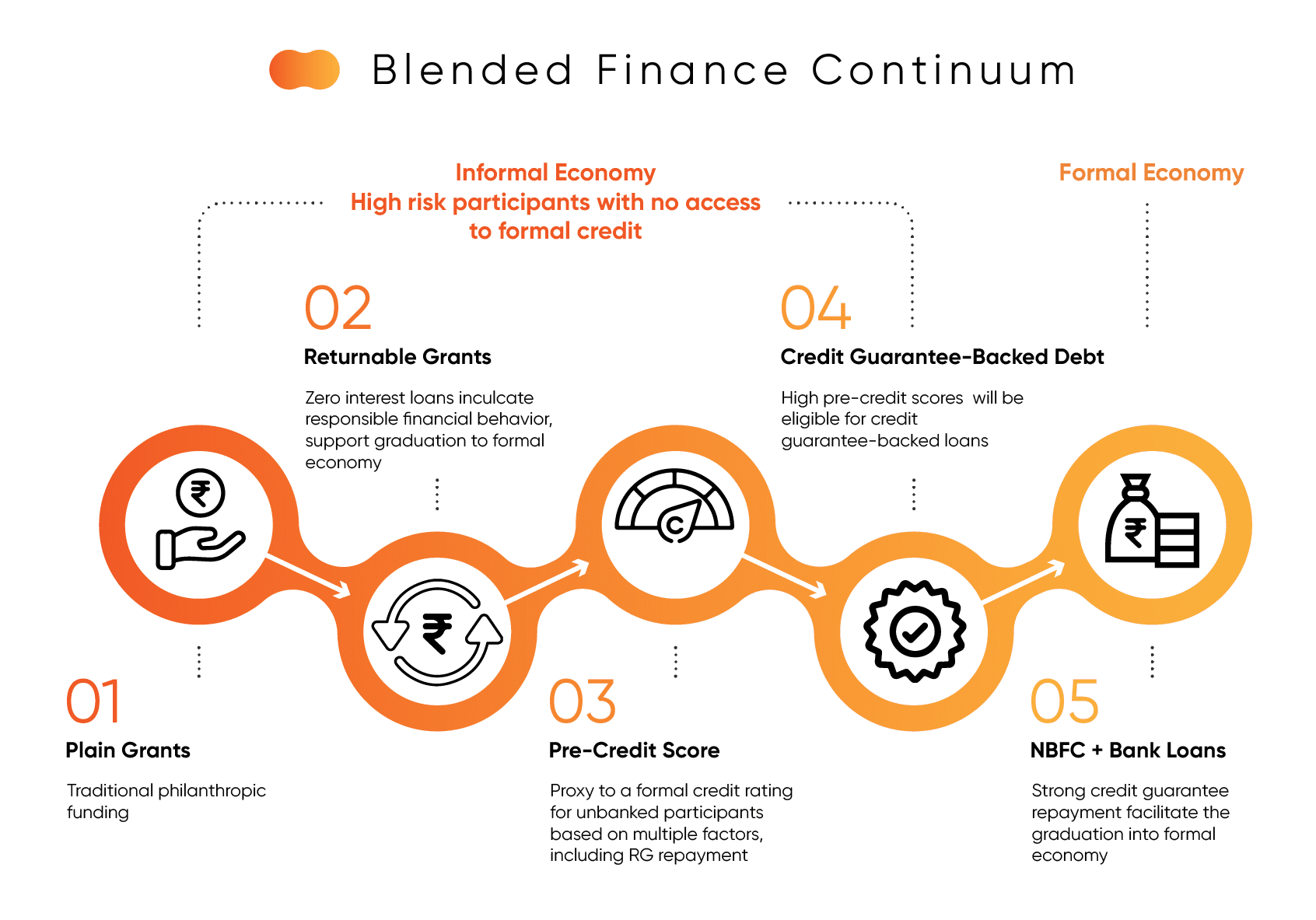

The innovative approach of a blended finance continuum can be a catalyst and pathway towards accessing future formal credit, driving economic growth, and providing financial inclusion for underserved communities.

In this blog, we will explore how the Returnable Grants, in conjunction with a pre-credit score, and credit guarantee, has the potential to create opportunities to transform lives for those in the informal sector.

Blended finance continuum: Opportunities or graduation into the formal economy

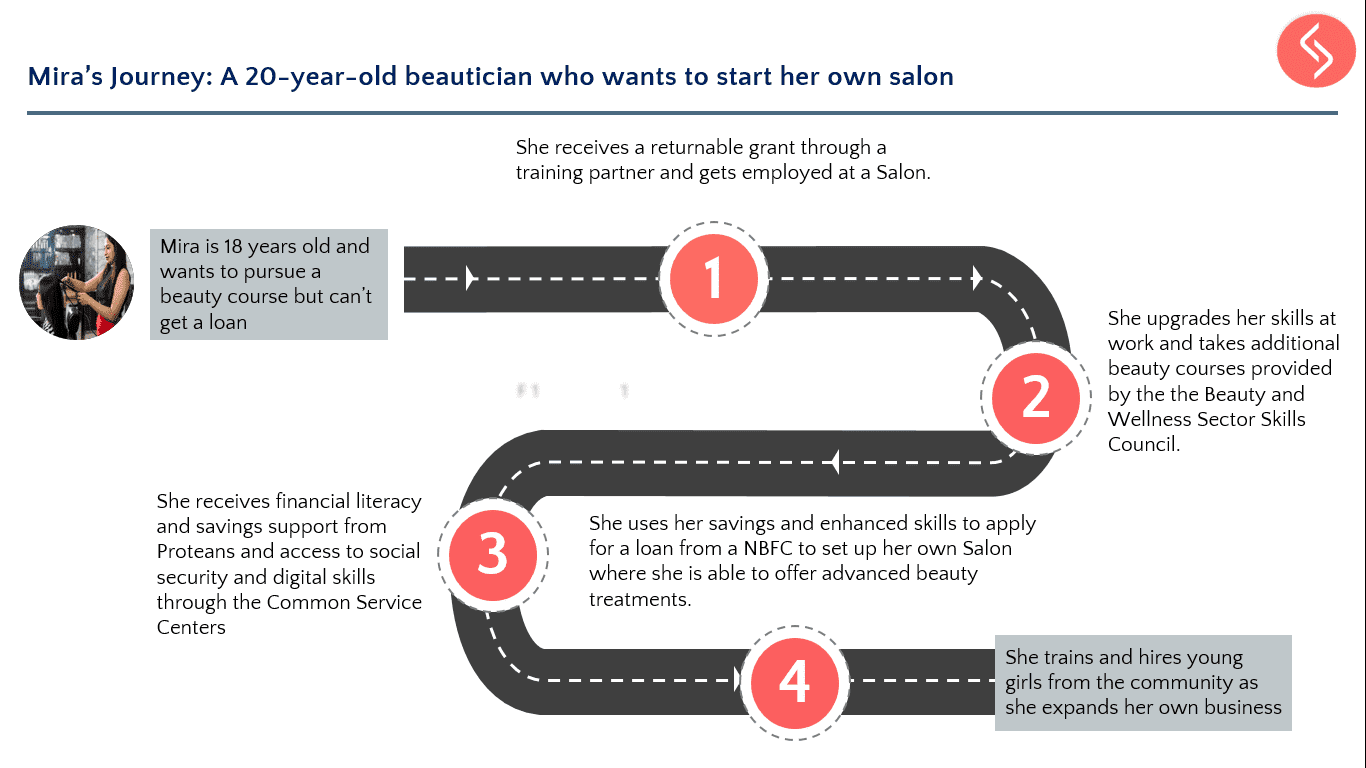

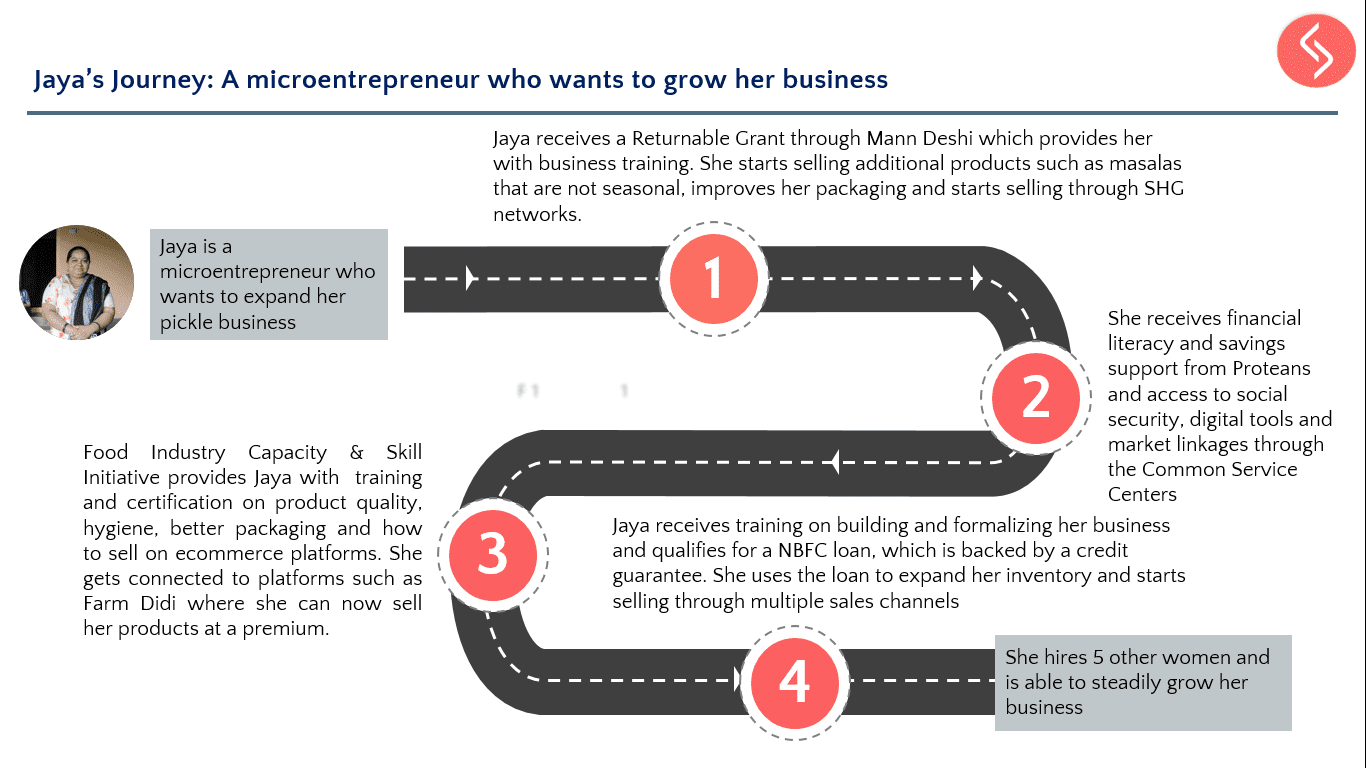

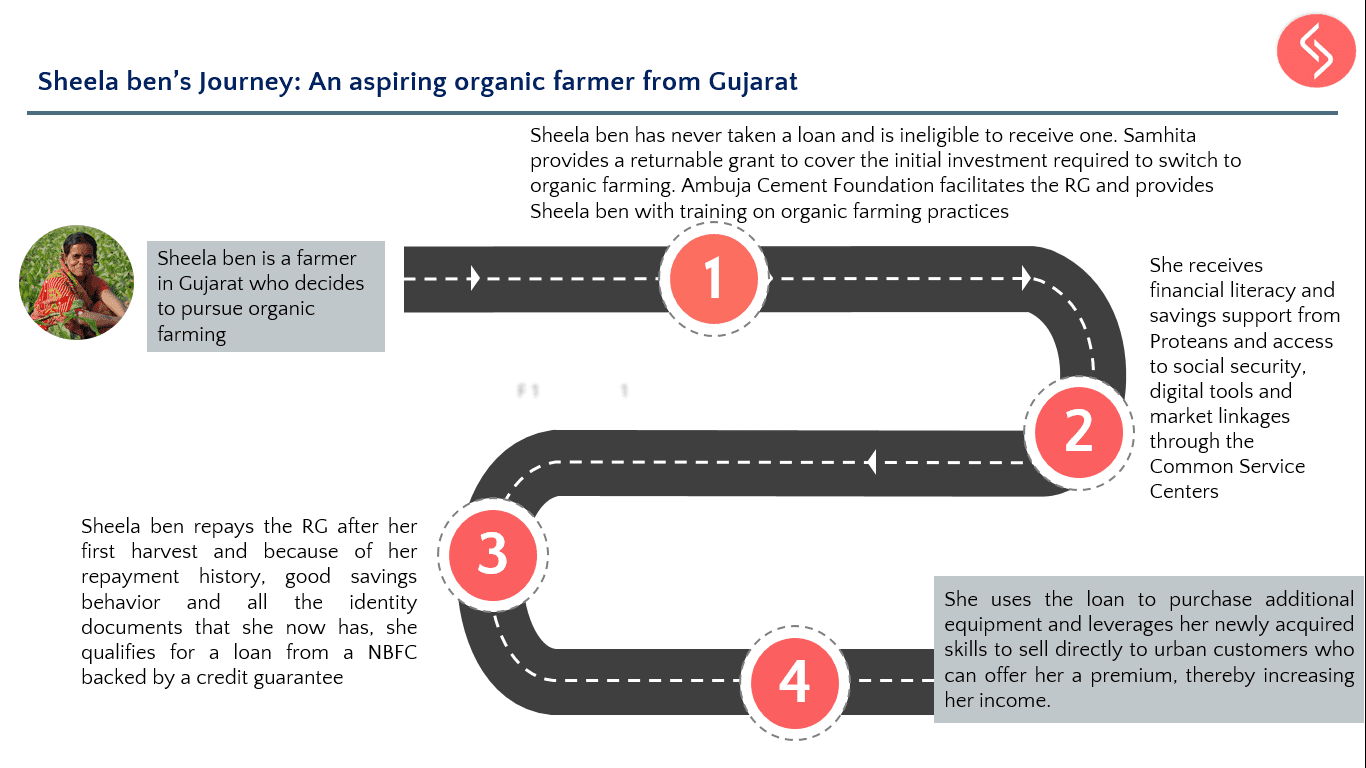

The blended finance continuum offers a progressive pathway for participants to move up the chain of financial instruments from grants to commercial debt. As participants repay grants, they build a credit history and become eligible to unlock more capital from mainstream financial institutions.�

The aim of the model is to eventually make participants eligible for commercial loans. A large proportion of women are first-time borrowers and don�t have the credit history, collateral or documents to take formal loans.�

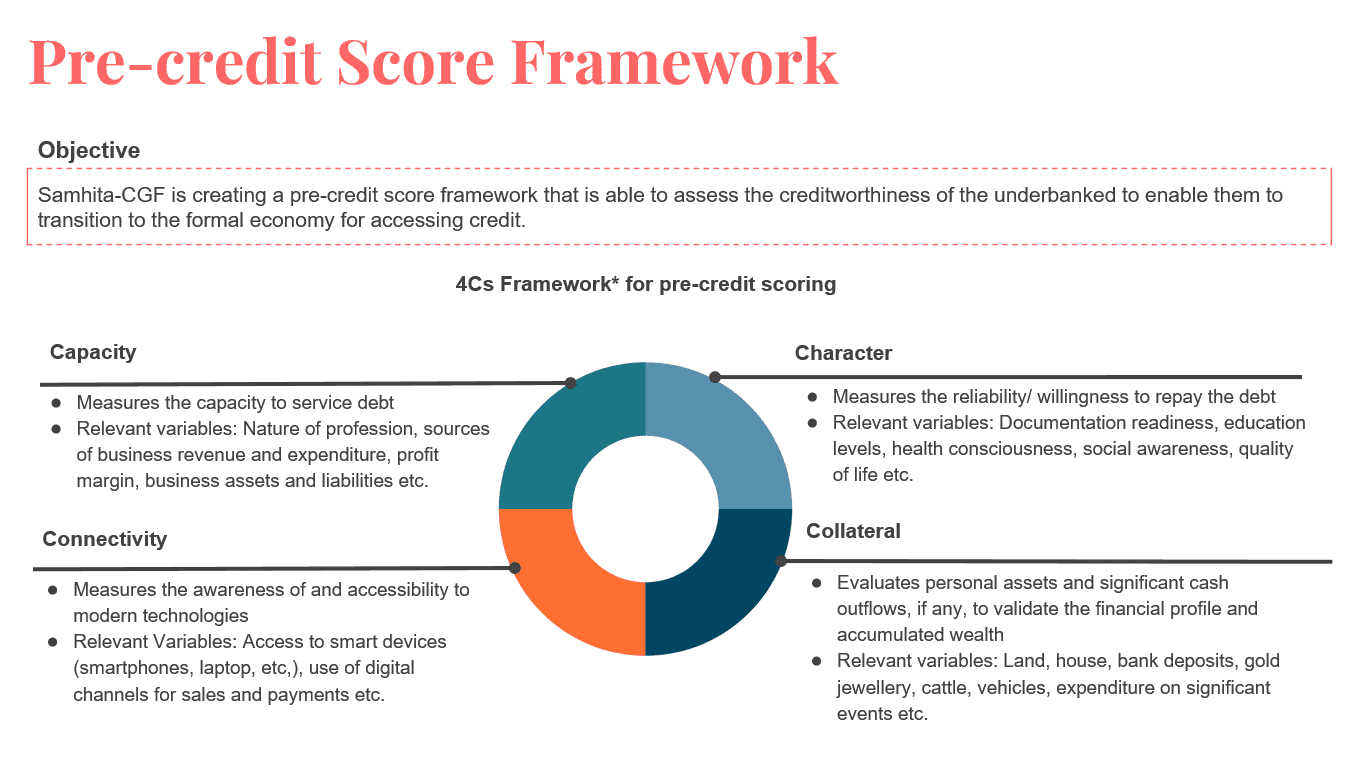

The pre-credit score with financial institutions and experts can be used by banks and NBFCs to offer affordable credit to first time borrowers; acting as a proxy for credit ratings and proof of ability to payback.

Paving the Way for Financial Inclusion

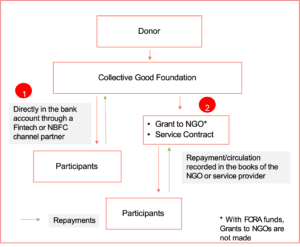

The Returnable Grants(RG) serves as a stepping stone for individuals and enterprises to transition from the informal sector to the formal financial system. By providing safe and flexible capital, the RG model enables micro-entrepreneurs, artisans, and job seekers to expand their businesses, invest in raw materials, and access new markets.�

As participants successfully utilize and repay the Returnable Grants, they build a credit history, gain financial knowledge, and establish their creditworthiness. This process aligns with the graduation model, which helps individuals progress from informality to formality, increasing their chances of accessing future formal credit.

�Fairoza Banu, a beauty-entrepreneur, used the RG model to expand her business. With the capital she received, Fairoza invested in high-quality materials and diversified her services. As Fairoza repaid the grant, she was able to show that she was able to pay back and be creditworthy.�

Pre-Credit Score: Unlocking Opportunities for New Borrowers

One of the significant barriers faced by individuals with no previous credit history is the lack of assets or creditworthiness. A pre-credit score framework is able to assess the creditworthiness and enable them to transition to the formal economy for accessing credit.�

Through evaluating repayment behavior and financial capacity, the RG model assesses the creditworthiness of underbanked individuals. Data collected from first time borrowers of the returnable grants along with other interventions can serve as a proxy to a traditional borrower..

This approach can provide first to credit borrowers with an opportunity to establish a credit history, demonstrate their repayment abilities and credit worthiness.�

Steps for building credit history:

- First-time borrower repays returnable grant/debt

- Provides access to financial, behavioral and repayments data which will feed into the pre-credit score

- Pre-credit score will be used to estimate repayment capability of the borrower when trying to avail commercial credit from Banks/NBFCs

�Repayment of the Returnable grant builds positive credit history and for entrepreneurs like� Fairoza, can put the on a pathway toward formalization to access formal capital, so that in the future she could potentially take formal business loan and expand her business, and even support in the creation of jobs as her business expands.�

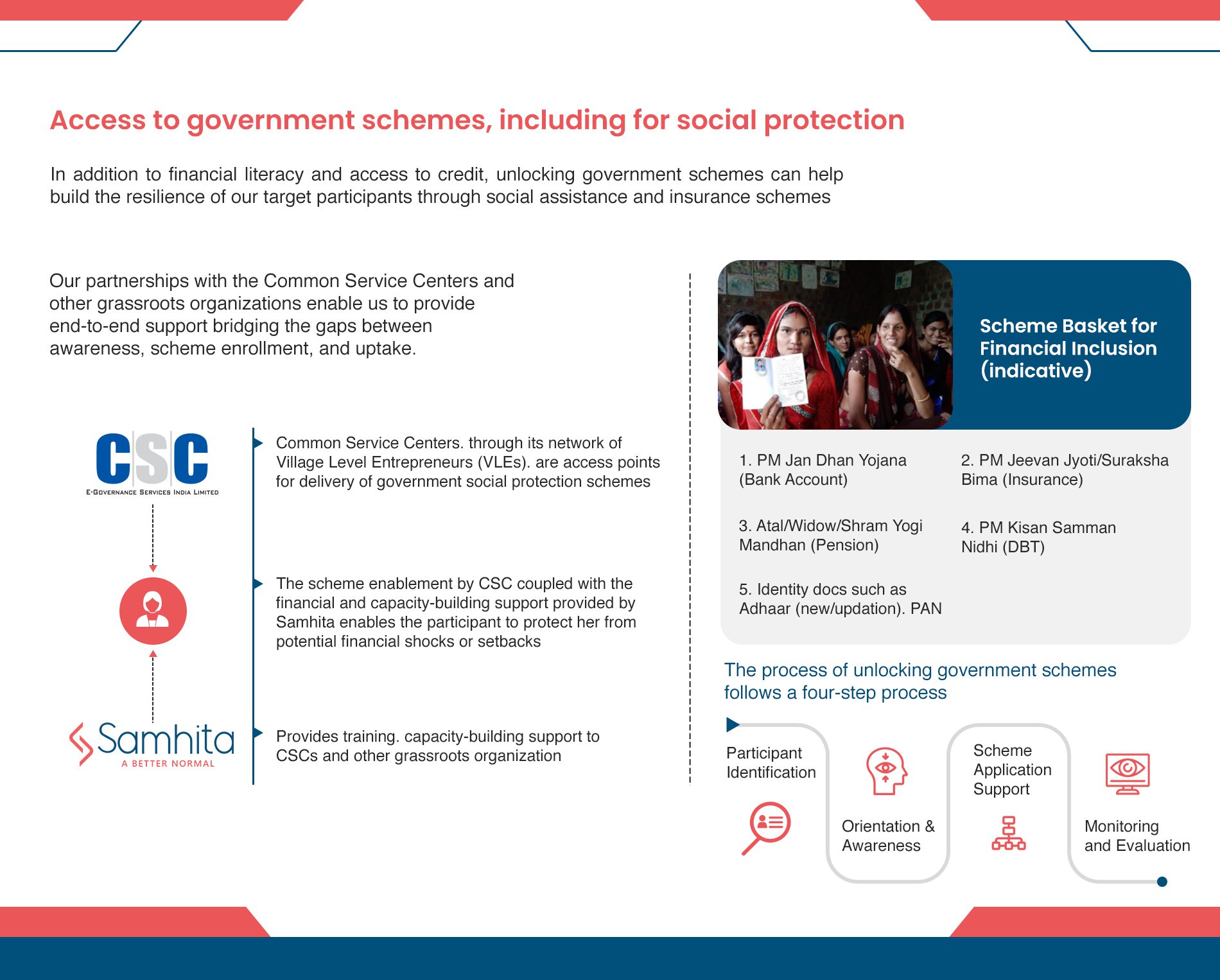

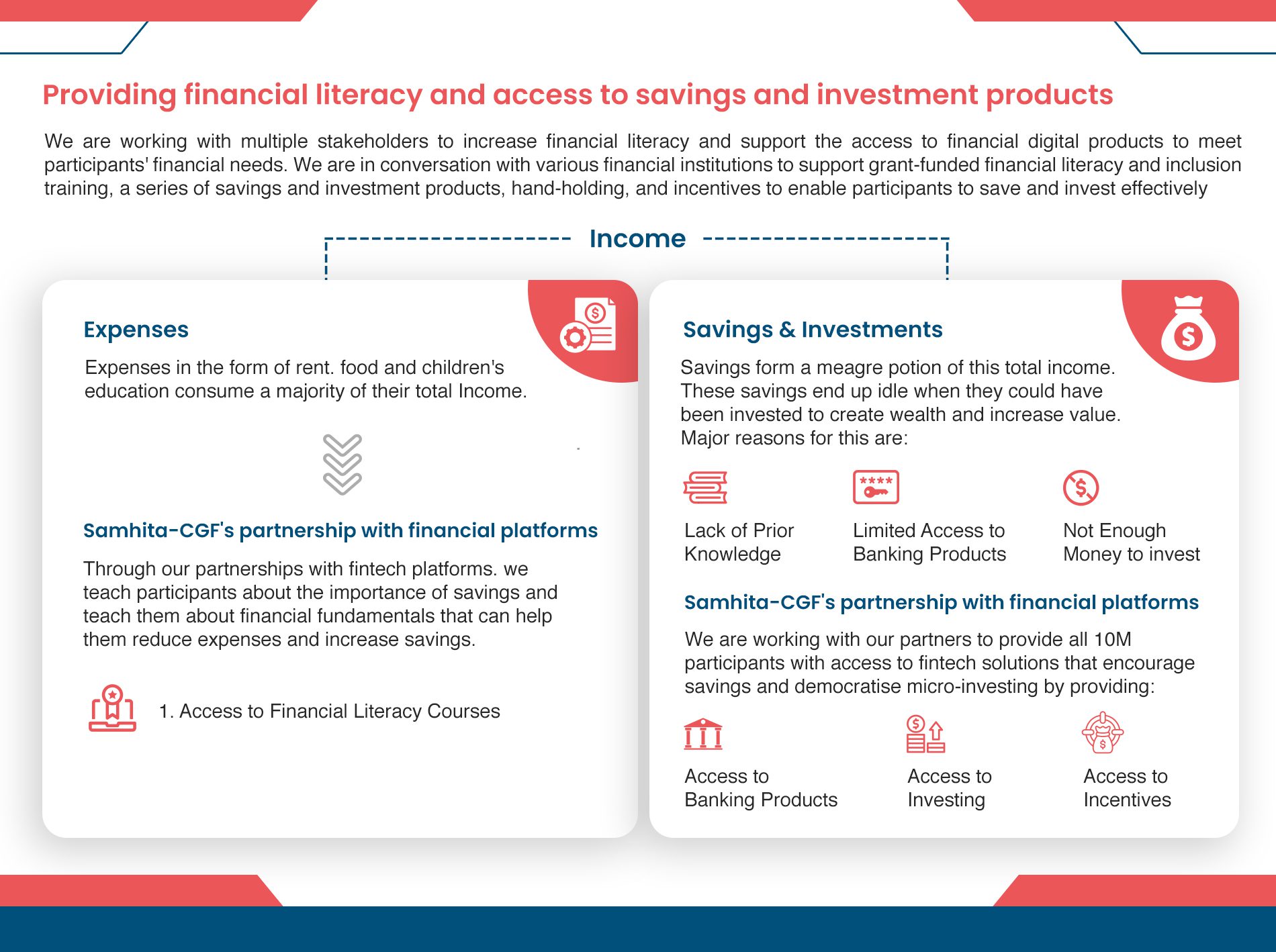

Improve access to relevant financial services on appropriate terms

A credit guarantee can mitigate the risk associated with lending to underserved communities and individuals. It acts as a form of assurance for financial institutions to provide formal credit to these marginalized groups.

- Risk Mitigation: A credit guarantee reduces the risk for lenders by providing a backup plan in case of default. This increased security will encourage financial institutions to extend credit to underserved communities who would otherwise be denied access.�

- Access to Formal Credit: A credit guarantee can bridge the gap between underserved communities and formal financial institutions, ensuring they have equal access to credit opportunities, establish financial stability, and become part of the mainstream financial ecosystem.

�As Fairoza�s business grows she may want to access higher credit amounts and access financial services, with a pre-credit score and a credit guarantee, a bank, confident in the credit guarantee provided by the RG model, can offer Fairoza and entrepreneurs like her access to great financial services. Such a collaboration can not only facilitate Fairoza�s growth but also encourage other financial institutions to support underserved communities.�

The Returnable Grant (RG), in conjunction with the graduation model, pre-credit score, and credit guarantee, has the potential to be a transformative approach to improve access to� future formal credit, increase economic growth, and provide financial inclusion for underserved communities.�

Through the graduation model, individuals and enterprises in the informal sector can overcome the barriers that traditional financial institutions impose on them,

- The Returnable Grant: acts as a stepping stone for individuals to transition from the informal to the formal financial system, enabling them to access future formal credit and expand their businesses.

- Pre-Credit Score: Evaluates repayment behavior and financial capacity of participants, to establish a proxy credit score, which paves the way for accessing formal credit in the future.

- Credit Guarantee: mitigates the risk for financial institutions, encouraging them to lend to underserved communities and fostering economic growth.

The impact of the RG model can be seen through real-life examples of individuals who have transformed their lives and communities.�

It has empowered women like Fairoza to access formal credit, formalize and expand their businesses, and contribute to local economic growth and her family�s needs.

Through partnerships with financial institutions and philanthropic agencies we aim to create public goods like the pre-credit score and credit guarantee facilities, and unlock the full potential of the MSME sector to drive sustainable and inclusive economic growth.

.

.